To my shame, before speaking with the sculptor Nic Fiddian-Green, I had little idea who he was.

I knew that most of his work was horse-based, large pieces of art commissioned to stand in landscapes, urban and rural, some private, others very public. I’d seen pictures of his studio, the artist himself, covered in dust, dwarfed by enormous bone-white casts of horses’ heads, tools in hand. I had read his résumé, and knew that a 1983 chance encounter with the British Museum’s Horse of Selene was where it all began, and that he has for much of his career been represented by the Slademore. Apart from this, I knew next to nothing about the sculptor Nic Fiddian-Green.

As I say, to my shame, because in a conversation that had him ruminate on the meaning of Goethe’s ‘absolute horse’, on the nature of the horse as symbol, as raw animal, on Morandi’s lifelong obsession with the painting of bottles, on the effect on his work of the death of his father, on art as inspiration, as a point of meaning, of what truly matters, on the risk of making I Will Look Beyond For a Distant Land (formerly Artemis), his biggest and ‘most important’ work to date, on so much, in fact, that has so little to do with the chatter of our daily lives, I quickly realised that I was in the presence of the real deal: a good man, a man of truth, a wanderer of the heavens.

By which I do mean to be absolutely romantic. I’m not a massive fan of the artist as starving, mad recluse, the Kafka myth, the tragedy of Van Gough. It’s not true (at least not without exceptionally long caveats), and especially not of artists like Fiddian-Green, whose monumental works require a small army of specialised help. His biography, when written, will include the encouragement of a father who slipped ‘charcoal sticks into my stocking’; the resistance of a mother who hoped for a lawyer-politician; a certain, enigmatic Mr White, an old school friend and early buyer, and who routinely introduced his then perfectly unknown friend-sculptor as ‘probably one the of greatest artists on the planet’; the ongoing support of family and friends, the hard-to-overemphasise significance of his greatest public champion, the Sladmore’s Gerry Farrel. It will, no doubt, note his Eton-educated background, and draw parallels between the horse, the landed and the few people on earth who can privately afford a sculpture worth the price of large house. In short, it will show, I’m sure, an artist in and of the world, a man more than capable of bridging the gap between maker and merchant, of taking his chances, of making his art pay for itself.

However, if that were all, then it would, at least from my point of view, fail to say anything about truth, the kind that Hunter S. Thompson might, were he alive and well, describe as being the result of a felt obsession, an intuitively driven hyper-elevating hunt, and one, once started, for which there is no normalising antidote, save a public retiring from art making – that or death itself. In his forward to Fear and Loathing in America, The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist 1968 – 1976, the late David Halberstam shines a powerful light on the nature of this particular truth telling, quoting both Johnson’s own sense of his making ( ‘my own style’) being utterly gonzo-controlled, a ‘junkie’ affliction for which ‘there is no known cure,’ and a letter in which he praises Fred Exley’s A Fan’s Notes , saying that ‘there is something very good and right about it’, that that something comes down to its ‘truth-level, a demented kind of honesty.’

Before you bulk at the analogy, and just to be clear, I know Fiddian-Green’s not a Thompson, at least not the drug-guzzling Thompson of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

For those of you yet to be acquainted with this brilliant alcohol-tobacco assisted author of the American Dream’s dark edges, Thompson was thin to scrawny, a street duke, a self-proclaimed freak, an amphetamine-fuelled habitué of airports and hotel lobbies, the reception rooms of the compromised great, the not so good. Fiddian-Green, meanwhile, is a character from a Saul Bellow novel, all muscle, all brain, a poet in blacksmith’s body. Both, however, are one of a rare kind, true to the calling, which for each or for any other artist worth a grain of salt is more a keening than a polite request. I’m second guessing here, but just as Thompson’s not sure that he actually likes Exley’s style, though recognises something great in A Fan’s Notes, so Fiddian-Green’s favourite work is the art that makes him feel the good of the world, that inspires, deeply and irrespective of movement, style or category. Such a work possesses none of the guerrilla-like social intelligence of a Hirst. Not for him an art that relies more on the ability to break codes than it does our capacity for wonder. Rather, it is a work that stirs the soul. It comes from belief. It makes the chest ache.

I’m getting mushy. This is old fashioned stuff; and opens itself to attack from all sides. Truth is relative. There is no good, no bad, only the biology of necessity. Granted, but consider this: as with the aforementioned Morandi and his bottles, or Cezanne and his love for a mountain called Saint-Victoire, or Yayoi Kusamo’s mania for spots, so Fiddian-Green has given his (artistic) life to a singular non-human muse. To borrow from Cezanne, he has seen the Horse of Selene, seen the horse as symbol, seen its visceral, savage, tender own-life beauty, and set about, through clay and metal, to learning how to see with his hands, to dissolve the distance between man and horse, to becoming, in essence, through its making, the horse itself. Put simply, he has communed – ‘gently’, over time, iteratively – with the other.

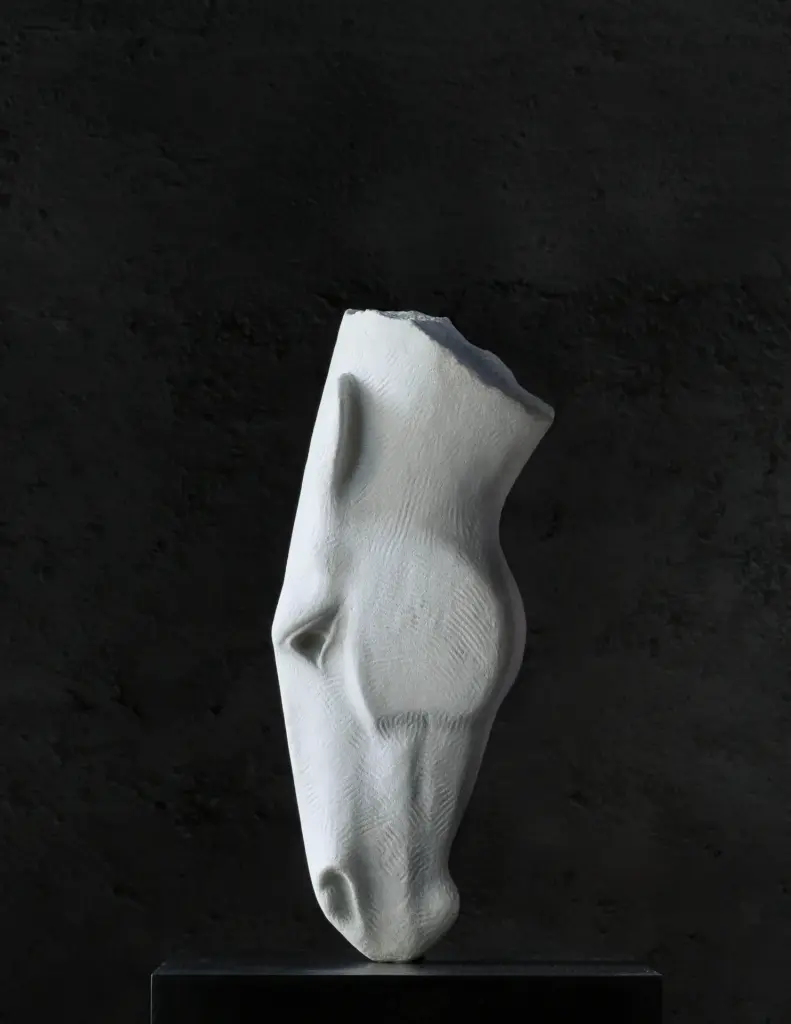

Fiddian-Green is typically light when it comes to explaining why horse and not anything else. ‘It could,’ he says of first meeting the Horse of Selene, ‘just as easily been a warrior’s torso.’ Perhaps, though it’s worth asking whether anything other than a horse could have carried the weight of 30 years worth of making. His is not an animal genre art. ‘The horse,’ says Fiddian-Green, ‘encompasses all symbols, all attitudes. It is the most important animal.’ It is ‘a vehicle for expression’. Nietzsche, who famously intervened at the sight of a horse being whipped in a plaza in Turin, hugging it and whispering ‘my brother’ into its ear, would have understood. Magnificent, brutal, wise, harbourer of the human’s secrets, its hopes and its dreams, its regrets, failures, its madness, the horse is the creative’s vehicle par excellent.

Easy to see, then, how Fiddian-Green’s ‘obsessive, introverted, compulsive… supplication’ of the horse remains so endlessly rich, and why as a subject it works on so monumental a scale. On size, Fiddian-Green’s explanation for the growth of his creations is entirely rational. The more successful he has become, so the greater the opportunity to make larger works. As with, however, and to push our analogy one more step, the effect once garnered by the space afforded Thompson’s gigantic articles, so the increase in the scale of Fiddian-Green’s work allows for the exponentially extraordinary effect of the horse as giant. If you’ve seen Still Water (Marble Arch, London, a frankly uninspiring city square), then you will know that the horse is big enough a symbol to be made a giant without losing all sense of its visceral aesthetic. A lyrical colossus, congruent, gentle, impossibly ethereal, it gains in size, at least for me, a certain mournfulness that I don’t see in the smaller pieces, at least not in the same way. It is a horse drinking and it is the sadness of the gods. It sees everything, the beginning, the end of time. This is death as peace, Elysium realised in metal. There is not, to paraphrase Thompson, an ounce of fat on it. It is another true horse; a new soul, uncovered. Anyway, I’m babbling. Go see it for yourself.

Attention, though. I say another horse, and not the horse. Listen to Fiddian-Green speak about his making, and the figure of a horse is ‘suddenly revealed’ not in essence, but rather as a form of expression, the result of having asked the right question, for long enough, and in the right way. He speaks of gazing into ‘the eye of a horse’, of ‘journeying into the soul’, but only, I think, as a means of it being a conduit for going beyond himself. The soul, in this sense, is not a thing, to be examined at arm’s length. Rather, it is that which ‘keeps us chasing’, the name for a mode or manner of becoming something other than one’s conscious self, a place ‘beyond man.’ It is beauty, inspiration, the holy self. Like seers, or Thompson’s mescaline takers, or the dreamer, or the seemingly mad, the artist can get us there, though in a different way, through the medium of his or her muse, an exploration of the potential of the creative human. For Fiddian-Green, that way is the horse.

Feature originally published in JOSHUA’s Magazine Issue FIVE