Jean Michael Basquiat is one of those artists whose mythology has somehow outgrown its medium.

In the same way Bob Marley is bigger than reggae or Elvis is bigger than rock ‘n roll, Basquiat is bigger than art. A common thread between artists of this ilk is that they didn’t set out to achieve this status. Their own iconography just ran away with them; at times shifting the focus from the art itself and onto the poster or T-shirt or keyring.

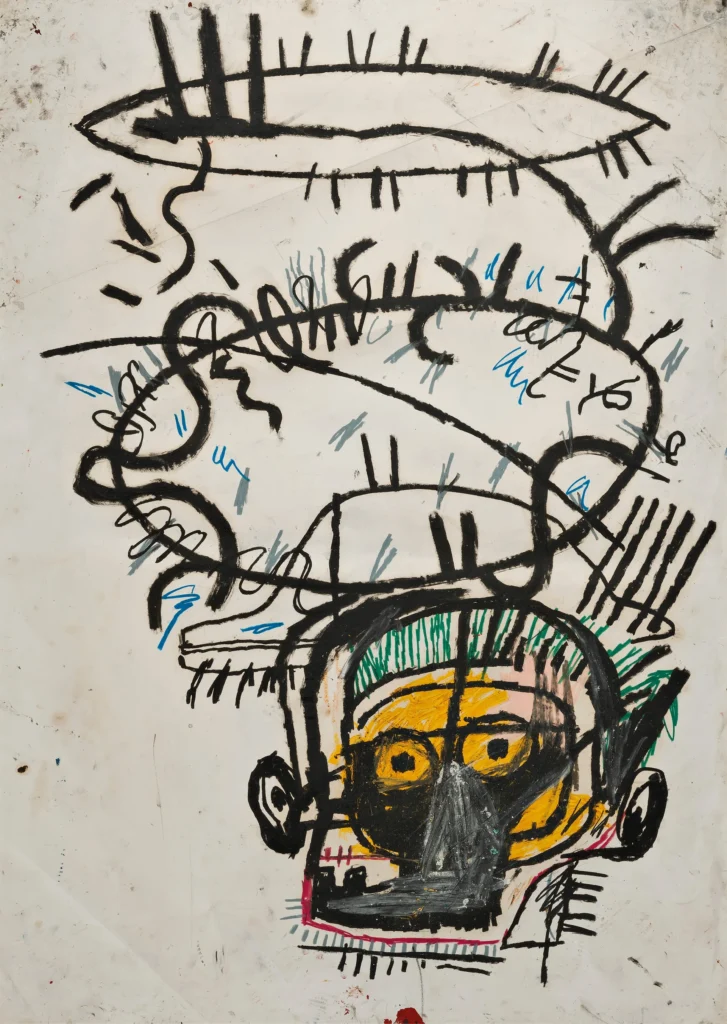

Head, 1982-1983

Oilstick on paper, 108 x 76.5 cm,

Private Collection.

© Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Courtesy of Colour Themes

Basquiat’s works delved into dichotomies between wealth, poverty, integration, segregation, and the inner versus outer experience. He approached his art without limitations – applying paints, poetry or painted poetry. Historical information is entwined and portrayed by way of abstraction, figuration and bombastic neo-expressionism. With an astounding balance of razor sharp nuance and outrageous visual pizazz, he lampooned structures of racism in a way that forced people to confront it.

His rise coincided with that of hip-hop and he was positioned as a progenitor of an explosively creative era that would crescendo in the 90s and then buckle and homogenise under the weight of the incoming internet age. Untitled – which depicts a black skull with red-and-yellow rivulets – is his masterpiece that shot him to fame. In 2017, it sold for a record-breaking $110.5 million, becoming first painting after 1980, and making Basquiat the youngest artist, to surpass the $100 million mark.

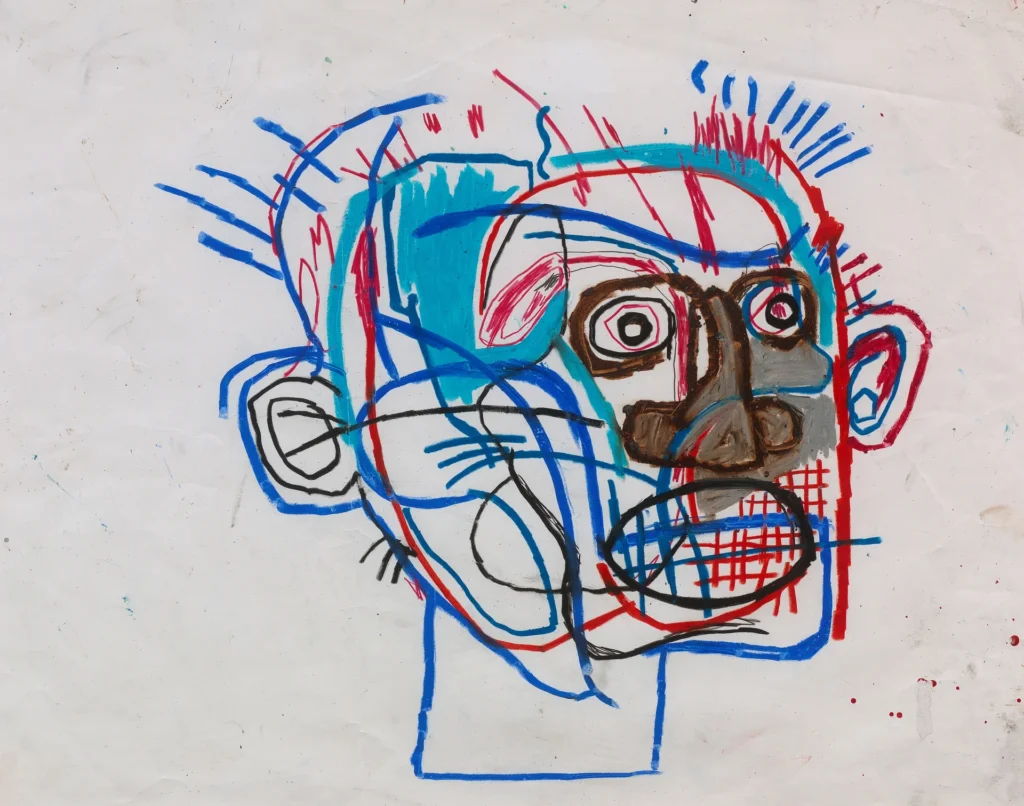

Untitled (Head), 1982

Oilstick and graphite on paper, 48.3 x 61 cm.

Private Collection.

© Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Courtesy of Colour Themes.

It is telling that many of his most revered works were untitled.

What’s in that anonymity? Fame is often the poisoned chalice that comes with greatness, and greatness often correlates with an indifference to fame. Basquiat died of a heroin overdose at 27, alongside other greats who derided their fame, and were perhaps driven to the grave by it. On his short time on earth he produced over 800 paintings and 1,500 drawings, most of which are rarely exhibited.

From Friday 30th of January, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark will be showing Headstrong featuring works by the legendary artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. Headstrong centres on works on paper made between 1981 and 1983, Basquiat’s most prolific and experimental period. During those years, the human head was a recurring motif. Revealing a fascination with anatomy, caricature and symbolic abstraction, the heads are a singular and productive contribution to Basquiat’s practice. The exhibition includes one single painting from this period – the aforementioned Untitled.

Untitled (1/2 Black, 1/2 White), 1982

Oil stick and gouache on paper, 76.2 x 55.9 cm

Private Collection.

© Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Courtesy of Colour Themes.

Basquiat’s heads can be linked to similar heads by modernist pioneers like Picasso and Klee, but they also reveal a fundamental interest in how the human interior is manifested in the exterior, reflecting ancient notions of spirit and flesh. The mouth, ears and eyes are conduits between outer and inner realities. Themes of excavating and X-raying are central. These are not traditional portraits but “heads” in a more expansive sense. Potentially representing Basquiat’s own subjectivity, they are snapshots of an artistic consciousness working overtime.

The nods to Picasso are obvious – playfully so. It is no coincidence that he is another artist who outgrew their medium, became a turn of phrase almost. Both Jean-Paul and Pablo were trying to figure something out; rearranging the furniture of their own minds to gain a new insight or perspective. They say fresh eyes can give us that breakthrough we were missing. Why not a whole readjustment of the head itself?

The drawings also offer insight into the pressure Basquiat was under, and the pressure he put on himself. He was just 27 years old when he succumbed to the weight of being a pioneer. As the artist Alvaro Barrington points out, Basquiat’s biography can easily be reduced to bullet points. But the wellspring of his success, his artistic talent, defies simplification.

Untitled, 1982

Pastel and oilstick on paper, 74.9 x 55.9 cm.

Private Collection.

© Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Courtesy of Colour Themes.

The heads were a private project and were unknown during his lifetime. Unlike Basquiat’s expansive paintings and collages, they reveal an introspective side to his work. The outside world appears to recede. There are none of his trademark symbols, writing or historical references. They are an introspective exploration, far removed from the loud, expansive works he released to the public. Markings show that he likely sat on the floor whilst he made these. Grounded and child-like in his process, one can imagine Basquiat engaged in the euphoria of creation; that most healing of states where the present and the doing is all there is. The clamour of the outer world that was to spur on his demise would have fallen away; and he was blissfully ignorant of the obscene commercialisation of his work in the years after he passed. Sadly, these states of being are fleeting, but their impermanence is a reminder that we never arrive, never stop becoming and, particularly in Basquiat’s case, with his works inspiring millions of us into a new millennium, never truly die.